My dear Albert Einstein, what's happening to you?

Einstein's afterlives continue to morph and change. How do we protect what we love most about this creative misfit?

Einstein's afterlives continue to morph and change. How do we protect what we love most about this creative misfit?

I’ve been thinking quite a bit about Einstein lately. Not about his actual science - I’m afraid that’s well beyond me! More about how he’s thought of today. About how people today come to know and learn about him, as a person.

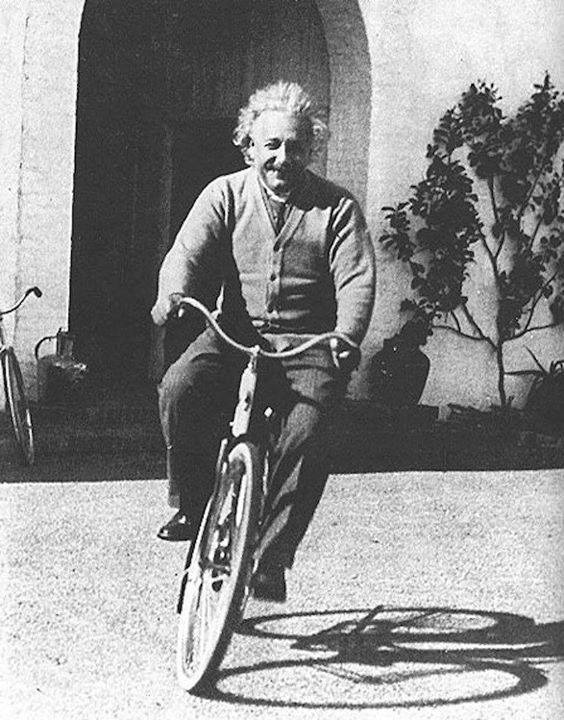

Like, as the the world’s most famous scientist who also loved riding a bicycle, with wind in his hair. Who said, in a much-loved quote: “Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving.”

I’ve been thinking of the version of Einstein you can explore online.

Einstein as vast trove of recordings, formulas, recollections, photographs, and letters that is continuously open to our changing narratives and stories of what it means to live, to learn, and to discover. Einstein is the guy we love to hold up and cherish, telling us how to be smart and sane and creative all at once.

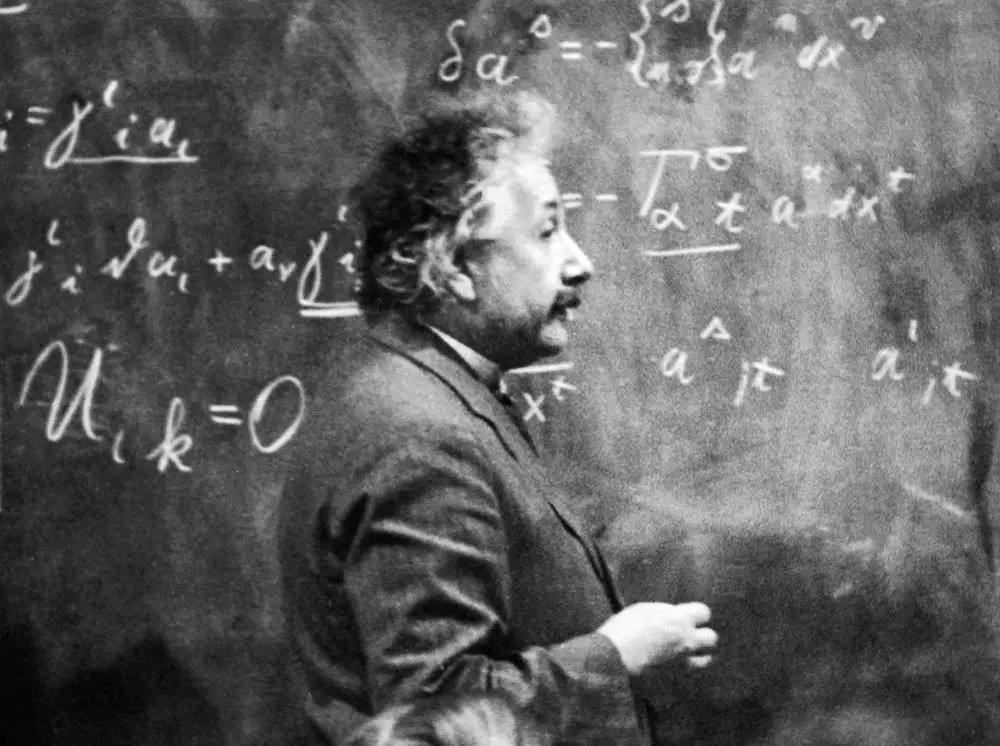

I suspect Einstein is who we look towards as the ideal of learning and imagination, of the power of a human to utterly change the world. Einstein used his mind to change how we understand the universe. Quite wild.

Because he’s so important, anything he created in his life is worth saving. Even his brain (more on that later)! There are vast troves of records and recordings of Einstein - 30,000 documents are now open access and available through the Digital Einstein Papers.

Not everyone has time to read all these records and letters, so we tend to rely on storytellers and historians to tease it out the data, the records, into narratives and stories we can relate to.

These stories - the many ways in which people look to Einstein for wisdom and understanding - tell us quite a lot about what we value in seeking knowledge, in achieving things, and doing the things that make humans quite great.

Anyone can be amazing!

Einstein’s life journey tells us anyone can reach the top of their field, if they try hard enough. It’s a crucial story we need in life to keep trying, against the odds.

The way the story goes, Einstein had trouble finding a job when he finished university. Also, he nearly didn’t get accepted into his preferred degree. After he graduated from the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich in 1901, he ended up at a patent office in Bern. It wasn’t as a tenured academic that he started to experiment with where his calculations could get him, but as a lowly clerk, with simple demands on his time, which enabled him free up his mind.

This story of Einstein has a lot of power. It reminds us that some of the most radical ideas in the world can come from the most surprising circumstances. It’s a story of hope and determination, too. No matter your personal circumstances, you can succeed if you try.

Imagination is everything!

Einstein was a scientist, but he cared deeply about imagination and curiosity, not just obscure mathematical formulas. He said, in one of my favourite quotes: “Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited.”

Einstein was also an accomplished violinist. He could easily have become a professional musician, not a theoretical physicist. Another great quote: “I see my life in terms of music”. Engaged deeply in the scientific complexity of music, Einstein was trained to look for harmonious expressions when crafting his theories. He took an aesthetic approach to theoretical physics.

Cycling is thinking!

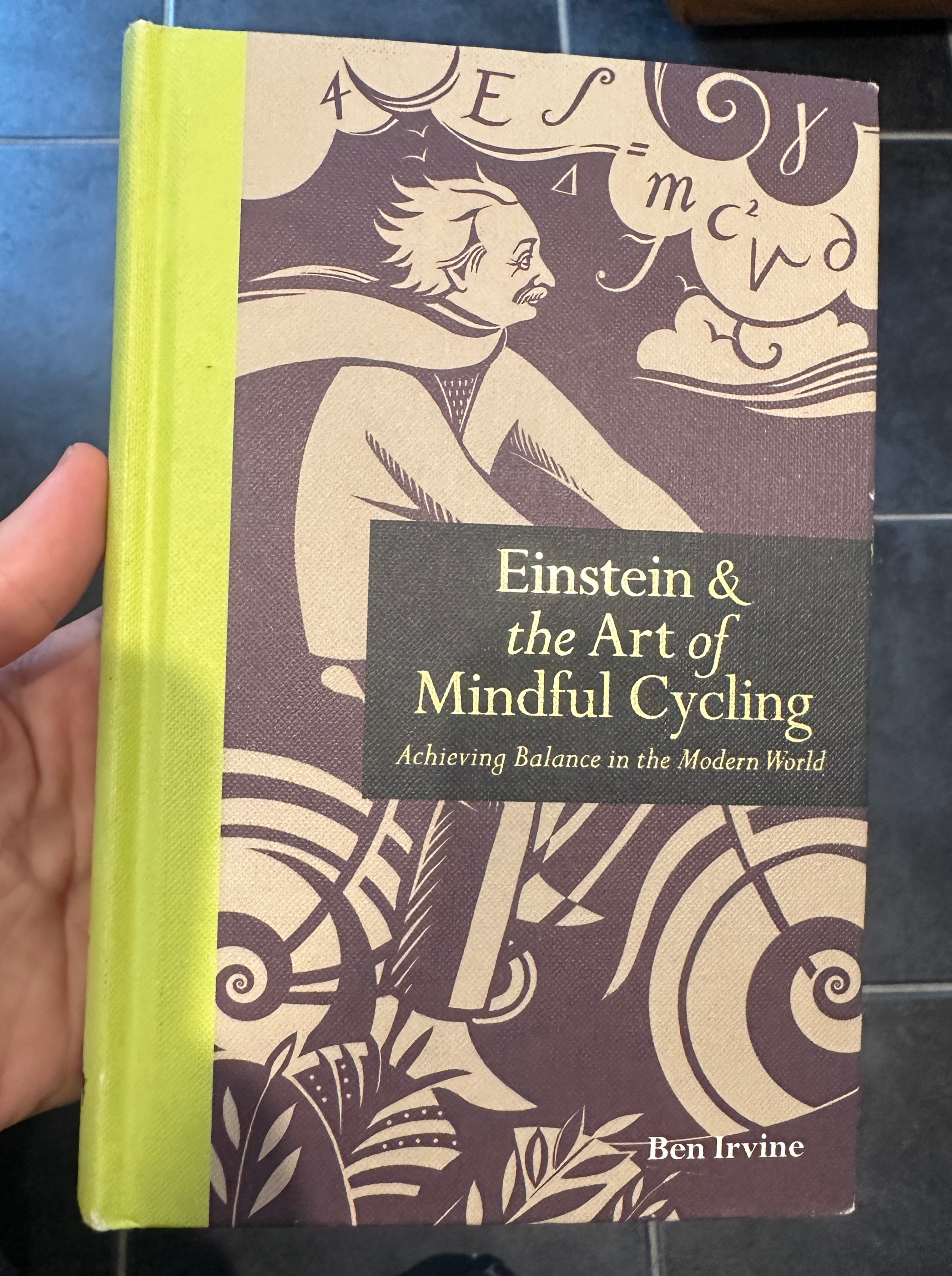

If Einstein used formulas to express his visual imagination, he still relied on sensory engagement and intuition to guide him. “I thought of that while riding a bicycle” said Einstein, commenting on his theory of relativity (retrieved quote thanks to the excellent Ben Irvine, whose booked I snapped earlier).

According to his second wife Elsa, Einstein would sometimes jot down notes and play at the piano simultaneously, lost in the worlds of art and science at the same time.

So Einstein was super smart, but he was also alive to the world of feeling. Here, he expresses the value of being an integrated human, sensing as well as knowing.

Ok, so there are other stories of Einstein we love less. Take the letters discovered by the granddaughter of Einstein’s his first wife, Mileva Marić, revealing an unkind man who cared little for her. In one of his letters to Mileva he wrote:

“A. You will see to it (1) that my clothes and linen are kept in order, (2) that I am served three regular meals a day in my room. B. You will renounce all personal relations with me, except when these are required to keep up social appearances.”

The letters Einstein left behind, now open access in our digital collections, show plainly how he was rude to both his wives. He was also unfaithful, and he preyed on young women. At least he regretted his behaviour towards Elsa after he died.

Indeed, the many narratives - the many afterlives of Einstein - continue to evolve and shift as time goes on. They hold a mirror up to how we think and learn today.

But, right now, they also point to how much we are changing what it means to think and learn today. And frankly, I’m terrified about what the future afterlives of Einstein might be turning into.

Here come the deep-fakes

The real Einstein is becoming harder to discern. Misinformation proliferates. There’s the supposed letter to his daughter Lieser proclaiming that love is the most ‘universal force’ in the world. Not a bad sentiment, but also, not true.

Einstein is a chat bot, Einstein is a deep fake, and there is even Einstein the deep fake detector. You can now create a voice that sounds like Einstein, trained on the recordings kept of Einstein’s voice. Would you like him to join your Zoom call?

The many afterlives of Einstein are splintering fast. All those recordings of him are training new learning algorithms, new versions of Einstein, which others are now using to interpret and make sense of the world.

Where is this all going?

The world in which Einstein lived sure feels different to the one we now live in. Like a world spinning rapidly away from this Earth, in another space-time continuum.

And today, in the rush to build new digital Einsteins, I think we’re losing the story of Einstein that matters the most. This is the story about how Einstein paid attention - and how his ability to pay attention completely changed the world.

In a strange and macabre twist, it appears even Einstein’s brain can tell us this.

It turns out that, contrary to his wishes, Einstein’s brain was cut up (‘sectioned’) into 240 separate pieces after he died. These pieces were then distributed throughout the US for study and investigation (in fact, against Einstein’s wishes). Some went missing, never recovered. Then, in the 1980s, photographic slides of these missing sections were found, leading to new studies into the nature of the brain.

(I wouldn’t share a photo of Einstein’s brain, by the way, because it’s against his wishes. I don’t think that’s at all appropriate or fair, if you respect Einstein in any way).

The photographs of Einstein’s brain reveal he had an extraordinarily large prefrontal cortex. This is the part of the brain known to process moment-to-moment input from our surroundings, allowing us to interpret them based on what we know already, and to act. It’s central to the control of attention, inhibition, emotion, and complex learning.

I’d like us to pay attention to this part of Einstein, and what we can learn from him, even today. Because in the rush to train non-human intelligence, we risk putting aside our own ability to interpret, make connections, and make sense of the world around us.

I see this in my own girls’ schooling. I see them being taught to write paragraphs using structured methods like TEEL, without being taught how to cultivate love and fascination towards their surroundings. Not how to consider a harmonious way to represent what they see around them, as Einstein learned to do, through his unique combination of musical training, mathematics, focused attention, and imagination.

We know that the digital landscapes occupying many minds today are changing how our brain actually works, showing changes to the prefrontal cortex in young children.

No doubt Einstein - the many versions of his life we learn, the thousands of stories, recordings, letters, data points we know about him - will keep changing. The data generated by the fake Einstein’s will grow and proliferate and interact with many.

My hope, though, is that Einstein’s afterlives can continue to teach us why we should value attention differently.

Why we should nurture it, like a special gift. Our prize.

We humans can be well trained to pay attention through the lens of beauty and imagination. We can learn from Einstein the value that comes from losing ourselves in the joy and magic of the waking moment, alive to the potentials to create and discern the harmonious arrangements all around us.

Even if we might be making things up, Einstein showed us that a little bit of magical, inspired thinking might be just what we need to make some kind of clear sense of the world.