Mystical language loops: A moment with Walter Benjamin

A refreshed newsletter focus for 2025, and an actual-imaginary encounter with Walter Benjamin to guide a mystical love of language & storytelling.

A refreshed newsletter focus for 2025, and an actual-imaginary encounter with Walter Benjamin to guide a mystical love of language & storytelling.

Picture this. You’re walking down the footpath, phone in hand, scrolling the morning emails. It’s the morning ‘house cleaning’ routine, clearing out the junk and spam accrued from the night before. Delete Delete Delete.

You’re walking down the street in a town called Melbourne, Australia. The bluestone tiles you walk upon are cracked and uneven. You are looking at your phone as your feet negotiate the uneven surface. Because, well, you know you can.

Today, you’re deleting without mercy. You want to feel in control of your life. You want to feel like you’re one of those zero-inbox people who walk this earth. It won’t change the immovable, immense substrata that is your unread email collection, but it still feels good.

Then you hear a voice, it’s his voice, speaking to you just now.

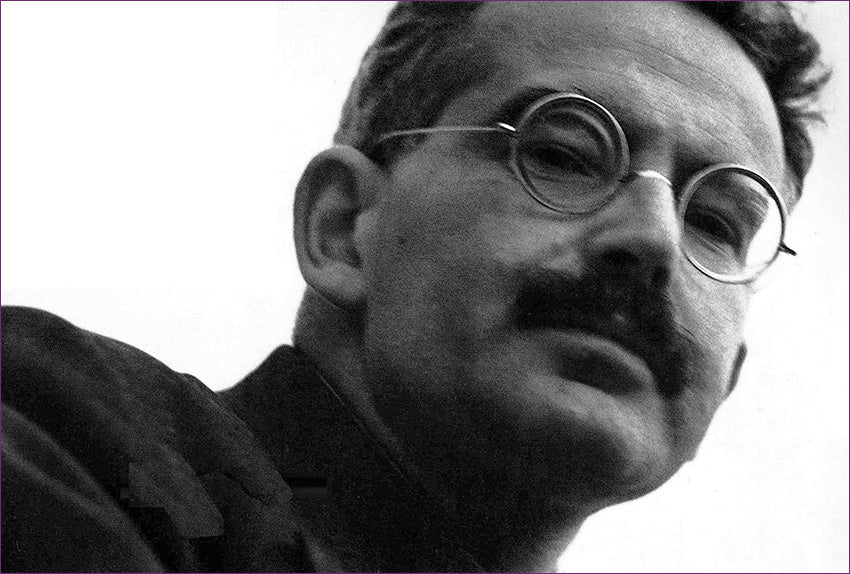

Gasp! It’s Walter Benjamin. The one you could never let go of.

A German philosopher and cultural critic born in the closing decade of the nineteenth century, Benjamin is the thinker you may speak to all your days.

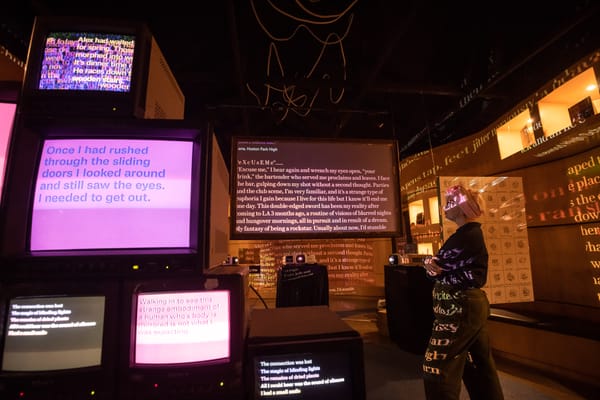

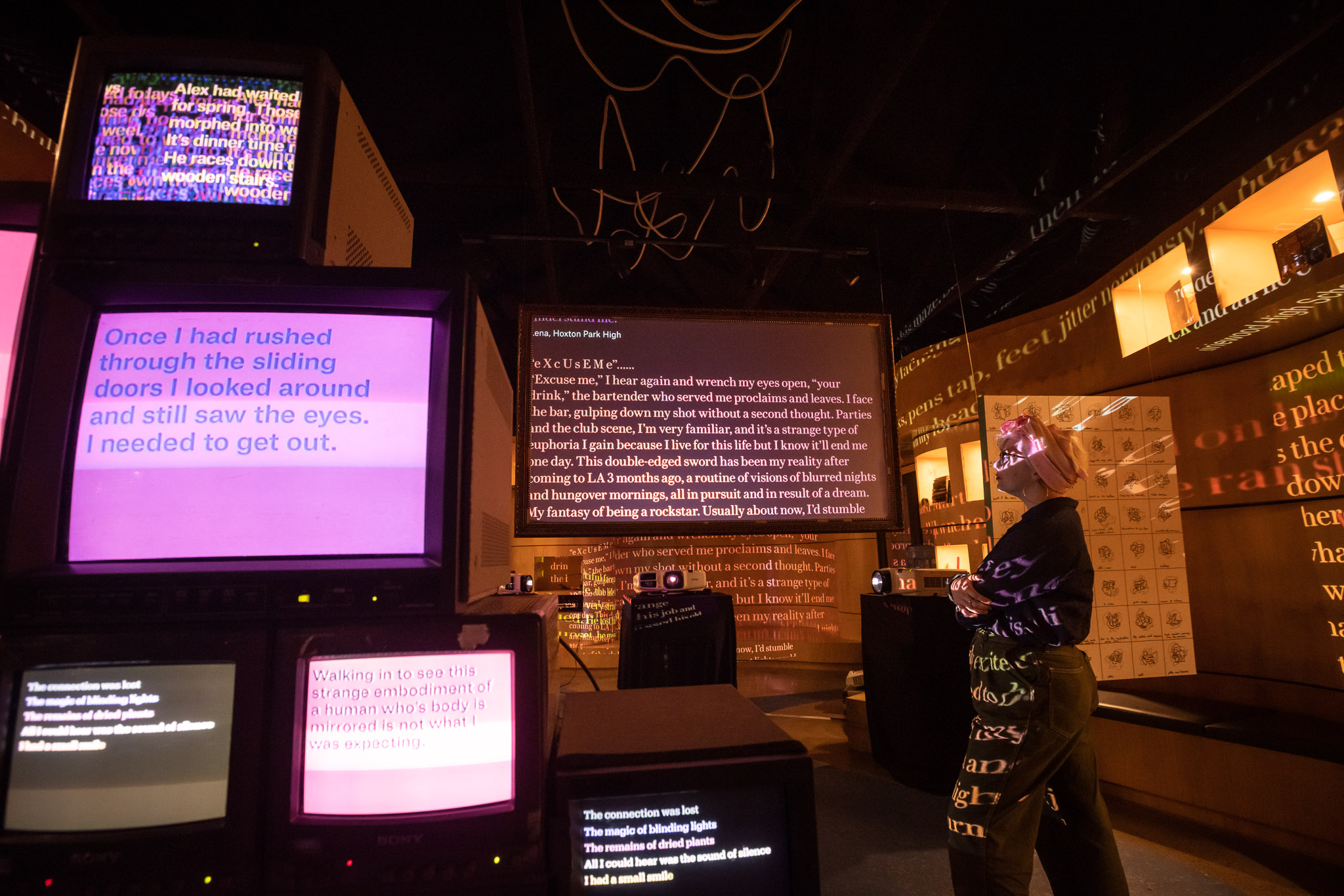

Benjamin, who used his love and adoration of language to express, in both wonderment and dismay, the disorientations of the emergent machine age: the cacophany of voices on the radio, the clanging of the mechanical street cars, the bewilderments of the exotic shopping arcades popping up around his beloved Paris.

Benjamin, who saw through the tactics of journalistic jargon, its smoothing of the lively world. Which he saw as training minds everywhere to accept this version of events, the world painted by the mass-produced newspaper article.

Benjamin, who brought such care and devotion to the happenings of the world, and to what he saw as the radical remaking of the western mind. Who used the arts of memory to disrupt the steady-smooth passages of modernisation. Who was, perhaps, the first remix artist, who saw that strange insertions of the past could be a way to undermine the tyranny of the now, towards something more radical, more emergent, more unstable.

Here’s here with you, at this moment, in this strange infosphere modulating and shaping your days. This line of his, it will never let you go.

You turn his words around in your mind. What did he mean by that, really? When we have news of the globe surrounding us, how can we be poor in noteworthy stories? Why is he telling me this, now?

You’ve trained yourself on this way of thinking for some time now. To let Benjamin’s disposition be your disposition. You’ve been taught to interpret the world as Benjamin would have done - which means to dispute, but not to suppress. Instead, to endow the everyday with something slightly magical and mystical.

Benjamin saw ‘noteworthy stories’ as the stories that shape the realities of our lives. ‘News of the globe’ is the information that spreads easily, but may not be what we need or value. News of the globe is the infosphere. As Benjamin saw it, people would increasingly need to negotiate between information and stories, between shared experience and its denial. They would need to discern the difference between the two.

Why did Benjamin call out to you just now, then?

You suspect Benjamin was asking you to pay more attention to how information is shaping you. Asking you to claim the right to craft your own particular version of events, your own story, not just the version brought to you from afar. To train your own algorithm, your own mind.

You imagine him saying: if our minds are constantly pulled towards formulaic announcements from faceless others, if they’re the ‘reality’ we’re taught to see as ‘real’, then what happens to the stories that will paint the sky and shape the faces of the people who come before us?

Benjamin played with forms of storytelling in ways that spoke to the deficits of his lived cultural currencies. In the 1930s, in the years before his untimely death by suicide at the French border in 1940, Benjamin walked away from academia, and wrote radio plays for children in Berlin. The Storyteller, his collection of short stories, was an attempt by Benjamin to move beyond the critic’s judgement, towards a more pure space of immersive, playful imagination.

If Benjamin was an advocate for the ‘return to the real’ in a world of globalising media, he also knew the work of doing this would require close attention to how stories and attention shaped experience and consciousness. In an essay “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man”, Benjamin wrote:

There is no event or thing in either animate or inanimate nature that does not in some way partake of language, for it is in the nature of all to communicate their mental meanings.

As Adam Kirsch put it in a wonderful 2014 NRYB essay (which, incidentally, rewired my brain when I first read it, waiting for my daughter to finish her swimming lessons, breathing in the heavy chlorine air): ‘Benjamin offered explicitly mystical conception of language as a form of divinely mediated exchange between God, men, and things’.

The perspective, you feel, is there to guide you in your life, as you face daily experiences of information overwhelm. To help you in this age of emerging Large Language Models (LLMs) and agentic AI.

No one, not even Yuval Noah Harari, quite knows how LLMs have become ‘self-aware’ so quickly. What kinds of mystical, divine practices will they reveal? Benjamin seems to be saying: these are ideas to play with, and practices to explore. Lest we become poor in noteworthy stories, our inboxes cluttered beyond all redemption.

*Quote is from The Storyteller, 147.

Thanks for reading Civic Interplay! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.